There’s a quote I love: “Practice, and all is coming.”

It’s true for so many things in life. You show up, do the work without clinging to the outcome, and one day—you realize you’ve arrived.

This is especially true in yoga. When we practice earnestly, willingly, and consistently over time, progress often comes quietly, almost unexpectedly. But when it comes to the physical side of yoga, there’s something important we need to consider: our bone structure.

Every day you step on your mat, you bring the same skeleton with you. No matter how many times a teacher adjusts you or how many hours you’ve practiced, your bones don’t change. And they set natural limits for how far we can go in certain poses.

The Role of Bones and Joints in Yoga

Paul Grilley, often called the father of modern Yin Yoga, explains that eight major joints of the body—wrist, elbow, shoulder, neck, lumbar spine, pelvis/femur, knee, and ankle—determine the range of motion for almost every yoga posture.

In yoga, we talk about two types of restriction:

- Compression: when bones meet and simply can’t move further.

- Tension: when tissues (like muscles, fascia, or tendons) resist stretching.

These are like the yin and yang of yoga. Understanding whether your stress in a pose is compressive or tensile makes all the difference.

A Living, Evolving Practice

Yoga postures should be dynamic, living things, just like your practice. A pose may evolve into something easier or more advanced, or it may stay the same externally while the internal experience shifts.

What feels right for one person may not feel right for another. Two people can look identical in a pose but feel completely different inside. That’s why all variations are valid.

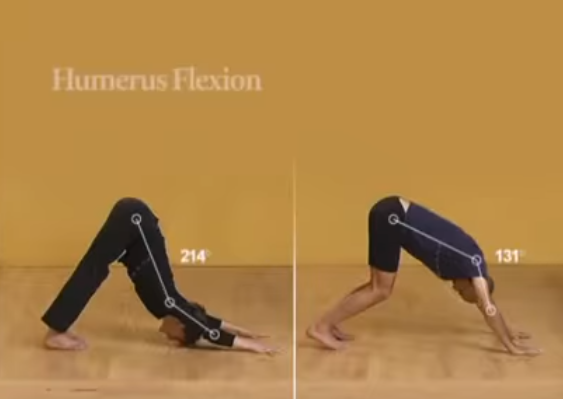

Take Downward Facing Dog, for example. When you raise your arms overhead, your humerus (upper arm bone) eventually meets your acromion (part of the shoulder blade). The length and shape of these bones vary from person to person. So even if your muscles and tendons are flexible, your bones might prevent you from moving into a “picture-perfect” version of the pose.

Knowing Your Limits

When this is the case, the wise response is to say: “This is my limit because this is how my body is shaped.”

Pushing past skeletal boundaries can lead to inflammation and injury. And remember, most yoga injuries don’t come from one big mistake—they come from repeating the same harmful patterns over time.

A Reminder from Yoga Philosophy

This brings us to one of yoga’s most important principles: Aparigraha - non-attachment.

Maybe the greater practice isn’t achieving the perfect Downward Facing Dog at all. Maybe it’s learning to let go of the idea of achieving it.

So I’ll leave you with this question:

Which is more important in your practice—getting deeper into the pose, or releasing the need to?